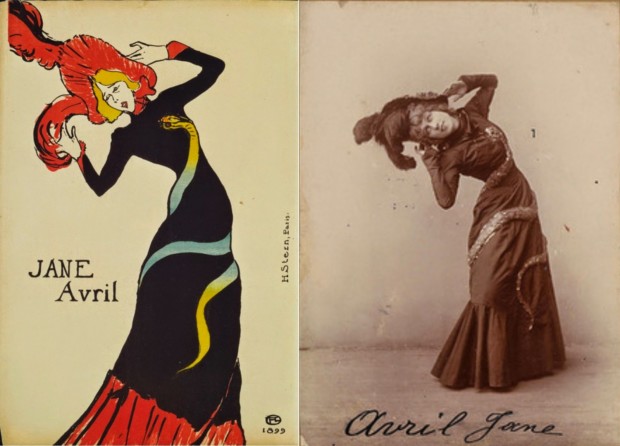

Jane Avril is positioned right at the point in which the history of psychiatry meets the history of art. She was a dancer in the late 19th century, immortalized by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec in posters advertising her performances. She was apparently an eccentric dancer given to jerky movements and strange postures. Before her fame, she had spent time as a patient in the salpêtrière.

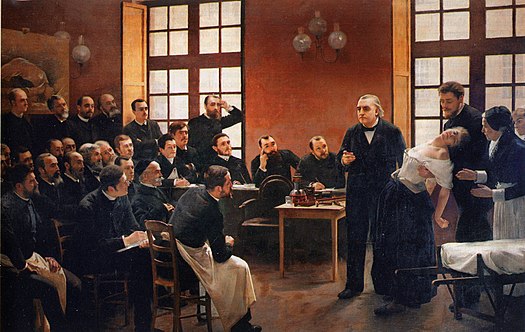

While she was there, an event momentous for the world of psychoanalysis was taking place. Martin Charcot, probably the most eminent of 19th century neurologists had stepped away from his laboratory and was now working on a particular behavioral disturbance which was then called “Conversion reaction” This involved a patient losing some physical function with no medical disorder. Thus a patient could be blind with their ocular system completely intact. They might suffer a paralyzed limb without anything being wrong with their bodies. Charcot would hypnotize these patients, and under hypnosis, he would bring the disorder to a halt. The “blind” could see, the “lame” could walk. What exactly he was trying to prove is now no longer clear, but his lectures were world famous and his students included Sigmund Freud and Pierre Janet. Freud and Janet started to get ideas of an unconscious or subconscious mind as a result of these lectures.

When I took psychology 101, the textbook had a reproduction of the above painting. It said the painting was famous, whether famous or not, the painting did show this man with an attractive helpless woman draped over his arm. There was a sexual charge to this, which was missing from my chemistry classes and it started me thinking about psychology as a profession.

It turns out that Charcot worked with patients at the salpêtrière who had been hospitalized with what we would now call mental illness. Patients at the salpêtrière were not well treated and volunteering to be an exhibit in Charcots lectures led to much better treatment. The patients were well rehearsed; they knew what was expected of them. In fact if you did a good job of swooning and acting blind, you received special attention. it also seems that these patients – all young women – were getting into sexual relations with the medical staff of the salpêtrière

Jane Avril was one of these patients. Based upon her later dancing, we might assume that she gave a particularly traumatic performance. She married a doctor and drifted into show business and Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings.

If we jump forward some 70 or so years, I was a psychologist wondering where the “conversion reaction” had gone. Freud certainly told us he had a bunch of them when he began his practice. But in the 1960’s, no one had ever heard of or seen such a patient. There was a rumor that there was a conversion reaction patient in Puerto Rico and maybe a couple in Israel, but they never materialized. In fact, there was no sign of them when researchers looked over hospital records that went back decades. It seems that Freud and his closest followers were the only people to have seen such cases. Historians also have at various times traced back the records of Freud’s patients and interviewed relatives who remembered them. They obtained the patients’ letters to friends. The patients indeed had problems, drug addiction, for example, but nothing like Freud’s description of them appeared. It seems that the idea of conversion reaction and Freud’s description of the origins of psychoanalysis were colorful fiction.

The only thing real about it was Jane Avril’s dancing.

Some decades ago, someone commented that psychology research was leading us to learn more and more about less and less. It was predicted that a time would come when we would know everything about nothing. That time has probably come. I’ve been retired now for some time but when I am brave enough to look at a psychology journal, I find studies of monumentally obscure behaviors being subjected to enormously complicated statistical programs that throw unlikely conclusions all over the place. Sometimes I imagine myself as an outfielder chasing down a flying outlier variable trying to catch it before it disappears.

All science may be correlated in one form or another. The world knows that correlation is not causation. Thus nailing down a cause may be a question for theology.

Leave a comment